Last month I highlighted some good research done by Lal Zimman at the University of Colorado, where he found two conceptions of coming out among trans people that were very different from the way the term is used by lesbians and gay men. In the comments, my friend Caprice Bellefleur hit on the next point that I was going to make: that there’s a fourth way that coming out is used.

There is a further complication about the use of the term “coming out” among trans people. Many, especially those who identify as crossdressers, use it to mean the first time they appeared in public in their alternate gender. They may not have disclosed anything to anyone.

In keeping with Zimman’s use of the letter “d,” with declaring a gender transition and disclosing a transgender history, I’ll talk about non-transitioning trans people displaying non-normative gender expression.

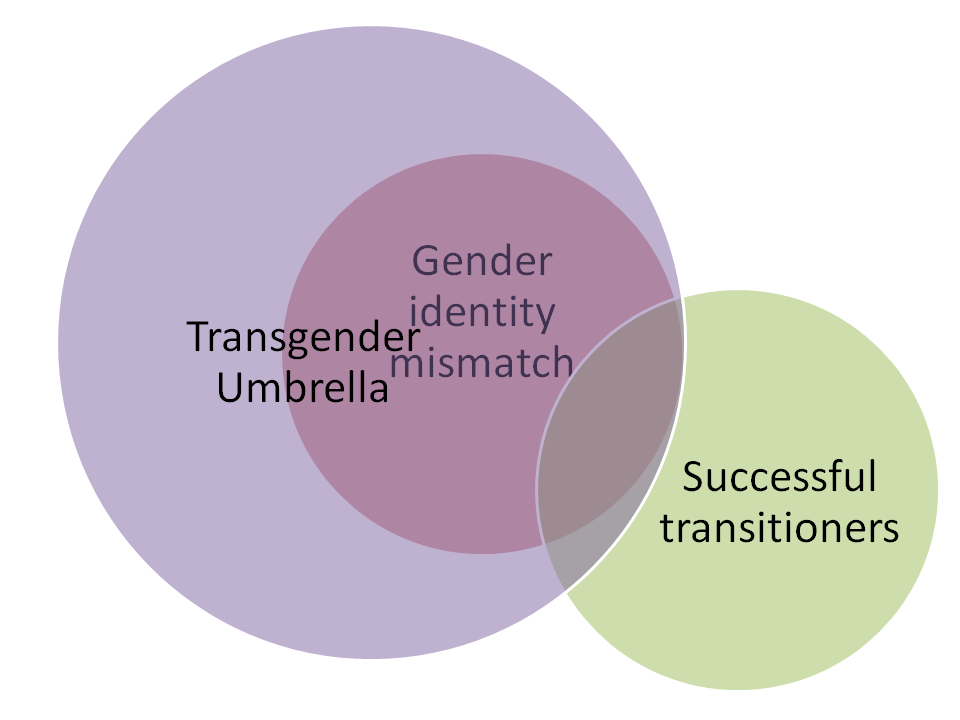

Zimman explicitly excluded crossdressers from his definition of “transgender,” acknowledging its use as a euphemism for “transsexual,” but when I met him in February I was there to advocate rejecting that sense of the word, based in part on the fact that there’s so much overlap. Many of his “transgender people,” particularly on the feminine spectrum, identify for years as crossdressers, and in fact the “declaration” he described is a performative speech act that, in the eyes of many trans people, is enough to allow someone to pass from “umbrella trans” (or even “just a cross-dresser” or “just a lesbian”) into “really trans.”

(I honestly don’t know much about coming out for queens and butch lesbians. I do know that for some gay men, coming out allows some feminine self-expression, and similarly allows some masculine expression for lesbians, but I’ve heard that that is still stigmatized by many people, gay and straight.)

As I said before, I’m not really happy with these three uses of “coming out.” To put this in perspective, there are several advantages that the “gay” kind of being out confers on the individual and the community:

- The dishonesty and self-denial necessary to be closeted tend to be habit-forming and have a corrosive effect on character

- The same habits of dishonesty and self-denial have a corrosive effect on the tenor of group interactions.

- Large numbers of gay men, lesbians and bisexuals being out contribute to safety in numbers.

- It’s easy to dehumanize people when you can pretend they’re not there, but it’s a lot harder when you know someone.

- It’s easy to hate people when they feel ashamed of themselves, but it’s harder when they have self-respect.

The two forms of “coming out” that Zimman describes (declaring and disclosing) fulfill all these characteristics, but they are only available to people who choose to transition and genderqueer or genderfluid people. Someone who has the exact same thoughts, beliefs and feelings but decides not to transition or change their primary gender expression has only the display form of coming out available to them. When people display they are visible in public as trans people, but in clothing and accessories that they normally don’t wear, and with makeup that changes their appearance. They may not be recognized by people who know them in their primary identity. Most importantly, they don’t use the same name. How is anyone supposed to know that the Tiffany Sparkle that they met at the dance club last Friday is the same person as Bob from Accounting?

This means that displaying has only one of the four advantages of coming out, the “safety in numbers” advantage, and that only when people are actively cross-dressing. There may be some feeling of liberation in this, but it is fleeting, and at all other times they still have to hide and to deny their true feelings. And while they hide, others are unaware that people they know are “one of those” and know that all these people are so ashamed of themselves they don’t want their true names known.

I seem to be the exception here. I decided not to transition in 1995, and I decided to come out in 1996. I came out “gay style,” by putting up a website and telling my co-workers. I didn’t start wearing dresses to work; I just told people. And when a trans-related topic came up, I came out again as necessary.

I’ve reaped three of the four benefits of coming out. I’ve felt hugely better being able to talk about this important part of my life, and knowing that all these people know and are still treating me with respect. I’ve used it to build bridges in my community and break down walls of hatred and mistrust. But I don’t get the benefit of strength in numbers.

I don’t know any other non-transitioning trans people who’ve come out the way I did, and that’s a shame. Because there are a lot of closeted trans people out there who don’t seem to know that it’s possible to come out this way. The only way they see out of the closet is to disclose a gender transition. That’s not right.