You may think you know what “transgender” means. But if you’ve been around the trans community for any length of time, you know that the word has been fought over before. There are at least three different ways that the word is used, and all apply to a somewhat different group of people.

First let’s take a look at one of the most widely circulated definitions, found in the GLAAD Media Reference Guide:

Transgender is an umbrella term for people whose gender identity and/or gender expression differs from the sex they were assigned at birth. The term may include, but is not limited to transsexuals, cross-dressers and other gender non-conforming people.

This is the famous “transgender umbrella” that we see in promotional materials and statistics. Note the “gender identity and/or expression” part – that’s the inclusive, welcoming part.

Now there’s another definition of “transgender” that conflicts with it. The funny thing is that it’s on the exact same page of GLAAD’s media guide, in the definition of “gender identity”:

Gender identity is one’s internal, personal sense of their gender. For transgender people, their birth-assigned gender and their own internal sense of gender identity are not the same.

In this definition, note that for transgender people – all of them – the assigned gender and gender identity are not the same. Those are the exclusionary, rejecting parts.

These two definitions contradict each other. The first one includes people whose gender identity doesn’t differ from our assigned gender, while the second one does not. They don’t both belong in the same organization, let alone on the same page.

There’s a third one, which was noted by Lal Zimman in his 2009 paper (PDF, page 58):

my use of the term transgender is not intended in the ‘umbrella label’ sense often found in literature dealing with issues of gender and sexuality. Nor is it intended as a pancultural descriptor to be applied to any gender variant community. Rather, my usage mirrors the meaning this term has taken on in many English-speaking transgender communities in the United States, in which it can serve as a demedicalized substitute for the term transsexual.

The GLAAD media guide notes that many people are substituting the term “transgender” for “transsexual,” and that not everyone is comfortable with that: “Unlike transgender, transsexual is not an umbrella term, as many transgender people do not identify as transsexual.” But then they give up on defining transsexual beyond that. Zimman provides a definition: “those individuals whose sense of themselves as men or women runs contrary to the gender they were assigned at birth, and who have therefore decided to make a social transition from one gender role to another (regardless of what medical interventions, if any, are pursued).”

I want to modify Zimman’s definition here, because he is mixing something that is observable (a gender role transition) with something that is not observable (a gender identity mismatch). His “therefore,” although it is widely claimed by many, is also unjustified. There are a significant number of people who transition to a new gender and report having no clear feeling of a gender identity mismatch (or even a gender identity at all) before transition; Zinnia Jones is probably the best known: “For most of my childhood, I didn’t feel like I had a meaningful identity of any kind, gender or otherwise.”

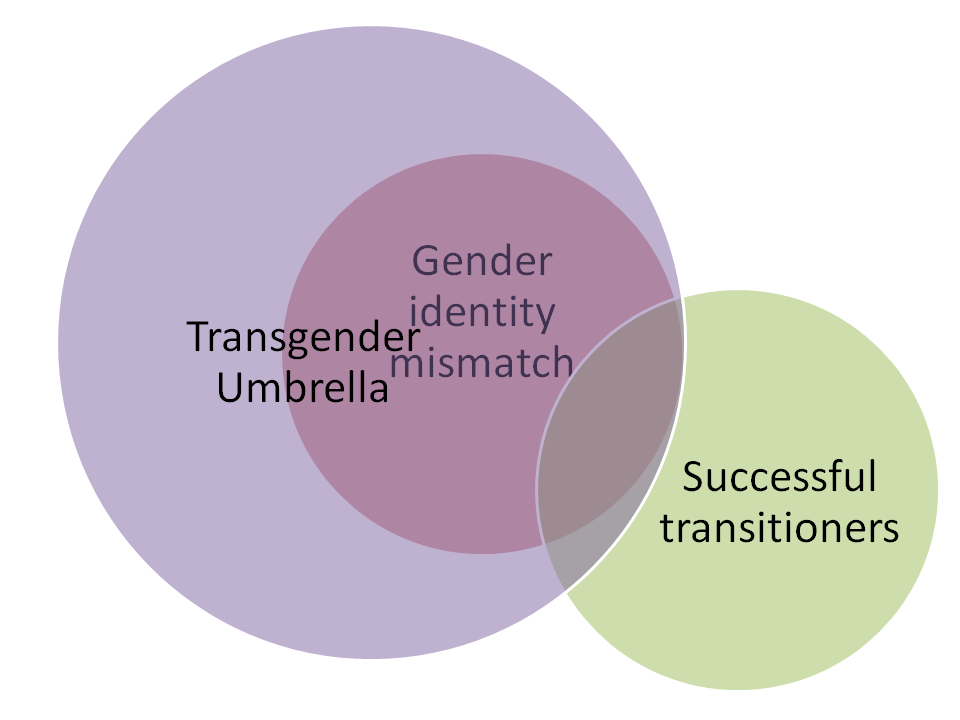

This leaves us with three definitions of “transgender”: the umbrella, the gender identity mismatch, and the transitioner. There is a lot more overlap among these definitions than the diagram above would suggest, but it remains true that there are people who fit under the umbrella who do not transition or have a gender identity mismatch. There are people who have a gender identity mismatch and fit under the umbrella who do not transition. And there are people who transition but do not have a gender identity mismatch or fit under the umbrella.

This is important to me as someone who fits under the umbrella but is not planning to transition. I hope that GLAAD will revise its Media Reference Guide to be more consistent with its stated goals of inclusion.